REA.A Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions & Support to Experts A.3 MSCA Staff Exchanges

Some considerations on the concept of informality in the ILO

Highlights

The 21st ICLS definition of the informal economy excludes activities whose goods or services are prohibited, such as human trafficking or drug trafficking. It includes production that becomes illegal when it is carried out, for example, without authorization, such as the execution of construction works without the required building permits (Frosch, 2024b). This conceptual delimitation contributes to the development of a policy-relevant concept of the informal economy, aligning it with the formal economy. Thus, the idea of the informal economy becomes a notion that, to some extent, overlaps with, but also differs from, other concepts such as the unobserved economy or the illegal economy.

In the actual practice of economic activity, the "regular" and the "irregular" do not constitute watertight compartments in each productive unit or financial agent. That is, a producer can simultaneously generate both underground and emerged goods or services, a recipient of income obtains formal or informal income in the same period, and a consumer spends simultaneously on both regular and irregular consumption from an accounting perspective. The demarcation line between the two sides of the system, economically speaking, is not clearly identified with any single economic entity, but rather all (or many) participate at some point in both.

In short, from an accounting perspective, the flows of production, income, and consumption are equivalent for the economy as a whole, but not necessarily in each of the two parts into which we have subdivided it, "black" and "white." Neither are the flows of money from undeclared activities (black money), nor the value of undeclared production or consumption.

SOME CONSIDERATIONS ON THE CONCEPT OF INFORMALITY IN THE ILO

Santos M. Ruesga

KEY WORDS: UNDERGROUND ECONOMY, INFORMAL ECONOMY, ILO, 21ST INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON LABOR STATISTICS,

Underground economy and informal economy

National Accounting systems attempt to assess, in monetary terms, the value of the production of goods and services generated by an economy in a given space and period. However, they suffer from a series of shortcomings in estimating this value, the causes of which we summarize below.

On the one hand, there are economic activities that generate value and, by definition, are not included in the national accounting framework. They are of four types.

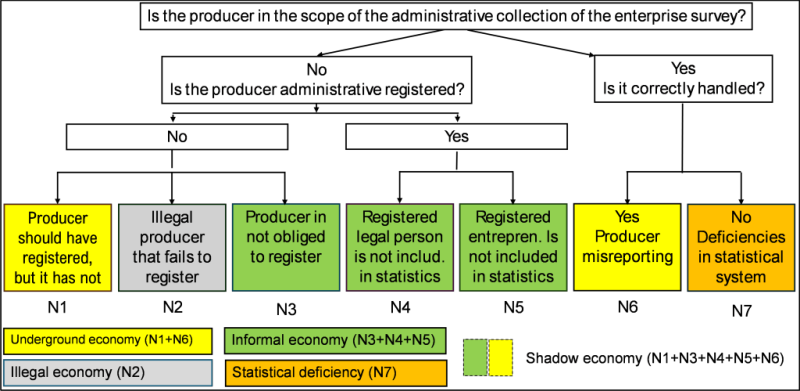

In the first group, we must consider all types of criminal activities not included in the estimate of the Gross Domestic Product or any of the aggregates estimated by the National Accounts. These are activities carried out outside the law, such as trafficking in prohibited substances, trafficking in persons, theft, extortion, corruption, and others. Consequently, no systematic measurements or estimates of their value are made by the respective accounting bodies. That is, these are illegal activities, so the producer himself does not register (N2 in Figure 1).

However, in recent decades, estimates of these activities have been made through indirect methods, as the individuals involved are, for obvious reasons (criminalization), unwilling to provide information about them.

The European Union produces detailed reports, for example, on the trafficking of prohibited substances (different types of drugs), including information on consumption (demand), market prices, and other economic aspects. However, these reports are insufficient for estimating purposes in terms of National Accounts.

However, the 21st ICLS definition of the informal economy excludes activities whose goods or services are prohibited, such as human trafficking or drug trafficking. It includes production that becomes illegal when it is carried out, for example, without authorization, such as the execution of construction works without the required building permits (Frosch, 2024b). This conceptual delimitation contributes to the development of a policy-relevant concept of the informal economy, aligning it with the formal economy. Thus, the idea of the informal economy becomes a notion that, to some extent, overlaps with, but also differs from, other concepts such as the unobserved economy or the illegal economy.

Secondly, we should consider those activities not recorded in these accounts because they are not voluntarily reported by the agents who carry them out. Therefore, no quantitative information is available about their results (N1 in Figure 1). Alternatively, it may be that, even if these activities are recorded, they show erroneous information voluntarily issued by the producer and, therefore, are not included at their exact value (N6 in the attached graph).

Third, it may occur that in certain circumstances, the producer of certain goods or services is not required to declare such activity or its production, whether legal or for any other reason (ignorance, the scope of accounting mechanisms, etc.), and is not included in standard official statistics. We are then referring to informal activities not included in the National Accounts, a field characteristic of less developed economies with weaker institutional performance, which implies gaps in the records, or greater involuntary ignorance of registration rules. In short, a less evolved institutional culture with a smaller reach. This is what is more specifically known as the informal economy, as shown in the National Accounts (N3, N4, and N5 in Figure 1).

Finally, we must consider possible errors in estimating the goods and services generated, which can reach significant amounts, depending on the technical quality of the estimation mechanisms (N7 in Figure 1). These errors can result from excess or underestimation, encompassing both over- and underestimation of quantities and prices.

Figure 1. Eurostat’s Tabular Approach to Exhaustiveness.

Fuente: Eurostat. (2021).

Additionally, an area of ​​economic activity not fully considered in National Accounting refers to the production of households, or more broadly, to the output of non-commodified goods and services. The fact that the exchange of goods and services they produce is not carried out through monetary means makes their monetary value extremely difficult to determine. Only rarely is this aspect of household production considered in National Accounting, as is the case with the production of agricultural products for personal consumption, which indirectly estimates their quantity and value. Other self-consumption situations (production of domestic services, caregiving services in the family, etc.) are not considered in National Accounting. And no one is unaware of the quantitative dimension that such goods and services can have (Ruesga, 1988; Durán, 2012).

In the statistical definition of the informal sector, according to the latest standards from the 21st International Conference on Employment Statistics of October 2023, the ILO considers three sectors, a typology based on two criteria:

- The formal recognition or lack of formal recognition of economic units, and

- The final destination of production, market-directed or not.

|

Formally recognized economic units |

Production primarily directed toward the market |

|

|

|

Yes |

No |

|

Yes |

Formal Sector |

Formal Sector |

|

No |

Informal Sector |

Household and community sector self-consumption |

Table 1. New conceptualization of informality according to the ICSL.

Source: ILO (2024).

So ILO defines:

1) The formal sector. This includes economic units declared by various producers of goods and services for the consumption of others (corporations, quasi-corporations, public enterprises, formal non-profit institutions, household suppliers, and formal households not incorporated into market-directed enterprises).

2) The informal sector. This includes units whose production is primarily intended for the market to generate income and profit, but which are not formally recognized as producers of goods and services, other than those that produce for the self-consumption of the owner-operator household (informal households not incorporated into the market as businesses).

3) Household self-consumption and community production sector (HOC sector): This includes economic units that are not formally recognized as producers of goods and services for the consumption of others, whose production is primarily for household self-consumption or for the use of other community entities, households, but without the intention of generating income and profit (households and informal non-profit organizations) (Frost, 2024a).

Therefore, regarding the basic profiles of the phenomenon under analysis, it is worth clarifying that when we talk about the underground economy, we refer, in general terms, to the set of productive activities "not accounted for" in the conventional instruments used to measure the production of goods and services in a given territory and over a given period of time.

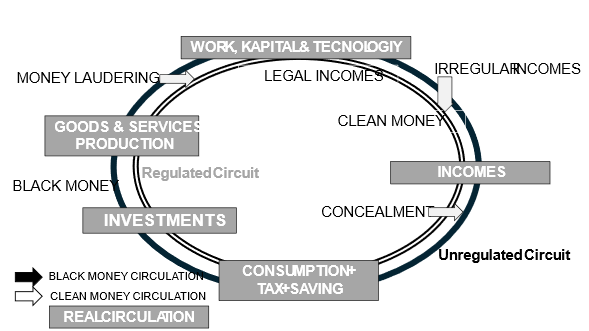

THE CIRCULAR INCOME AND MONEY FLOW

Now, the economic flow originating in this production generates, in turn, a flow of income that feeds another flow of consumption. If we had some mechanism for estimating each of these flows independently, we would see that they do not necessarily coincide in value; that is, "hidden" production does not necessarily coincide with the homonymous incomes that, in turn, end up in consumption or savings, whether hidden or not.

In the actual practice of economic activity, the "regular" and the "irregular" do not constitute watertight compartments in each productive unit or financial agent. That is, a producer can simultaneously generate both underground and emerged goods or services, a recipient of income obtains formal or informal income in the same period, and a consumer spends simultaneously on both regular and irregular consumption from an accounting perspective. The demarcation line between the two sides of the system, economically speaking, is not clearly identified with any single economic entity, but rather all (or many) participate at some point in both.

In short, from an accounting perspective, the flows of production, income, and consumption are equivalent for the economy as a whole, but not necessarily in each of the two parts into which we have subdivided it, "black" and "white." Neither are the flows of money from undeclared activities (black money), nor the value of undeclared production or consumption.

From another perspective, financial activity, which is fueled by savings but has its own capacity to expand its value through financial products circulating independently of the production of goods and services, may also include a certain amount of "black money," the exact amount of which does not coincide with the irregular flows of real activity for a specific period. That is, for the analysis and, above all, the calculation of what is generically called the underground economy, we would have to specify a priori what flow we are referring to.

Figure 2. Circular goods and services (real) and monetary flow

Source: Prepared based on Ruesga Benito, Carbajo Vasco, and Pérez Trujillo (2013).

We can start by examining the flow of goods and services produced within a given period in an economy. Therefore, we begin with an accounting identity:

Pt ≡ Ct,

Where P is total production and C is total consumption, both in period t.

If we consider the existence of unrecorded transactions, the identity will become:

Pt = Ptr + Pti ≡ Ct = Ctr + Cti

Denoting the subscript r as regulated production/consumption and i as informal consumption. And therefore:

Ptr≠Ctr nor Pti≠Cti

To determine the total value of production and consumption (including intermediate products), we would have to estimate each of these values independently. The same would occur if we refer to the production of final goods (GDP, suitable for final consumption), which generates income (Gross National Income, GNI), which, in terms of National Accounting, would be equivalent to the value of Final Consumption of goods and services (Final Consumption, CF).

Now, starting from the well-known Fisher Equation, which shows the equivalence between the total value of transactions (a price index, IP, times the total transactions carried out in a given period and in a specific space, Tr) and the means of payment used to carry out said transactions (the money supply, M, equivalent to the demand in the period, times a ratio that indicates the velocity of circulation, V, of those means of payment, the number of times a monetary instrument changes hands), that is:

IPxTr≡MxV

And considering that prices are similar for regular and informal transactions and that the velocity of circulation of the means of payment (generally money) is constant (which is also a big assumption, given the diversity of payment methods that should be integrated into the money supply (physical, electronic, or virtual money), we can conclude that:

IPXTr = IPrX(Trr+Tri)≡MV

Which could become:

GDPr+GDPi≡MV

Knowing the GDPr, estimated by the National Accounting System, we can deduce the GDPi from the available money supply.

Part of this money supply will be used for regulated transactions, and another part will be used for informal transactions (black money). When we carry out regulated transactions using black money (previously used for informal transactions), we are facilitating money laundering.

References

- Duran, M.A. (2012) El trabajo no remunerado en la economía global. Fundación BBVA. 1a. ed. Estudios Demográficos y Urbanos, 28(2), 525–531. https://doi.org/10.24201/edu.v28i2.1437

- Eurostat. (2021). Eurostat’s Tabular Approach to Exhaustiveness - Guidelines (GNIG/110). 5th meeting of the GNI Expert Group.

- Frosch, M. (2024a). Informal economy: A new statistical framework on the informal economy. Department of Statistics ILO. International Training Center.

- Frosch M. (2024b). Revealing the unseen: The 21st ICLS statistical standards on the informal economy. Statistical Journal of the IAOS40(4):767-785. doi:10.3233/SJI-240058.

- ILO (2024).Conceptual Framework for Statistics on the Informal Economy. ICLS/21/2023/Room document 1. ILO. file:///C:/Users/SR.5014038/Downloads/wcms_894151%20(3).pdf.

- Ruesga Benito, S. M.(1988). La mujer en la economía submergida. Información Comercial Española, ICE: Revista de economía, Nº 655, 1988, págs. 57-72

- Ruesga Benito, Santos M.; Carbajo Vasco, Domingo; Pérez Trujillo, Manuel (2013). La economía sumergida y el ciclo económico (The underground economy and the economic cycle). Atlantic Review of Economics: Revista Atlántica de Economía 2.1 (2013): 1-37. http://hdl.handle.net/10486/674694.

International Network for Knowledge and Comparative Socioeconomic Analysis of Informality and the Policies to be Implemented for their Formalization in the European Union and Latin America

Horizon Europe Project 101182756 — INSEAI 2023 REA.A

Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions & Support to Experts A.3

MSCA Staff Exchanges