REA.A Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions & Support to Experts A.3 MSCA Staff Exchanges

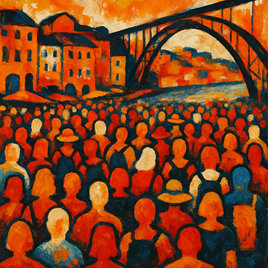

Saudade (touristized Porto)

Gabriel López y Javier Ortega

University of Alicante

Porto, with its cobbled hills, the broad flow of the Douro, and the shimmer of azulejo tiles, has in the past decade established itself as one of the most appealing destinations in European tourism. Yet behind the postcard image that millions of visitors consume and photograph each year lies a seldom-explored dimension: the realm of informal work that gives life—and perhaps authenticity?—to the tourist experience.

Margarida is 65 and sells cold drinks at her doorstep. Wearing an apron, without an awning or any other attraction, she has placed a table on the threshold where she serves tourists walking down toward the Ribeira. She worked for years as a cleaner; now she must top up her insufficient pension with the euros from tourism. One ordinary morning—because all mornings are ordinary when they repeat themselves—a young tourist stopped at her stall to buy a drink. The young woman decided to immortalize an image—a keepsake?—or, ultimately, evidence that she had visited an authentic place. She kindly asked Margarida to take a photo of her. Margarida, naturally, pointed to an old and beautiful mirror hanging just behind her—perfect for a postcard—and suggested she take a self-portrait in it so she would appear reflected, integrated into her own scene. But the young woman smiled and shook her head: “No, I want you in it.” She wasn’t looking for her own reflection, but for Margarida’s—the figure who, to her, represented the genuine essence of the place, the living postcard of a brief trip. She posed and took the picture, surely bound for one of the many Stories she would publish on Instagram. The encounter lasted no more than five minutes, perhaps the same duration as the fleeting memories of liquid modernity, as Zygmunt Bauman would put it. At the end of the day, Margarida’s son accompanies her to the supermarket to restock what she has sold. And what does she do when she finishes? “Nothing, I go straight to bed. Exhausted.”

In the last fifteen years, Porto’s city center has gone from half-empty to saturated. It wasn’t tourism that drove people out—at least not at first; the center had long been losing residents. The exodus toward the outskirts turned the city into an example of a “doughnut-shaped city”: life in the periphery, abandonment in the center. And that emptiness was taken advantage of; it had to be filled with a backdrop designed exclusively for its visitors. Starting in 2010, Porto became both a coveted destination for tourists and a magnet for foreign capital: the echoes of World Heritage status, two daily low-cost flights, several years as Europe’s best destination. What were once neighbors’ homes are now tourist apartments. No one walks their dog in the center.

Activity is frenetic, although this is not reflected in the calm, leisurely pace of tourists strolling through the city’s streets and squares. Activity is frenetic—and this indeed corresponds to the hundreds of workers who, day after day, strive to meet visitor demand. A substantial number of these workers carry out their activities informally, though not clandestinely. Rooted in art rather than in market logic (or is it?).

Carlos is a street musician—one among many who provide the soundtrack to the tourist experience. He has been playing in the city for 13 years: Rua das Flores, São Bento station. He remembers when there were barely a dozen musicians scattered across the city. Today he estimates there are nearly 200. “Now there are so many that it’s as if no one listens.” Supply and demand. This year the city council introduced a licensing system to limit where and how many artists can perform in public spaces. Carlos welcomes it. Everyone plays covers, nothing original. Airport music. “There’s one who plays Hallelujah [Leonard Cohen] ten times in a row. There’s even someone who has a playlist and pretends to play along.”

Porto hasn’t filled with inhabitants but with new uses. Licenses for tourist accommodation have skyrocketed. In some neighborhoods, up to 80% of the housing stock is tied to tourism. As with this global phenomenon, prices rose, local shops disappeared, and businesses catering to transients emerged. An amusement park for tourists searching for authenticity, only to bump into other tourists searching for authenticity. Duty-free sprawl—non-places. In just a few years, the city changed function; this is what scholars call “functional gentrification”: the city center becomes a product. It is sold, rented, beautified. Not necessarily in that order.

Jéssica is 28. In the mornings she works as a cleaner; in the afternoons she helps at her mother’s stall—cloths, souvenirs, caps, cold water. Her grandmother also used to sell around the neighborhood, down by the port, but the city was different then. “This used to be a neighborhood,” she says, “now it’s like a film set.” She points to the balconies with no clothes hanging, only plastic flowerpots. Selling there is not allowed, and sometimes they are fined. Among the vendors, they alert each other when they see police approaching. When that happens, Jéssica gathers the most expensive items and hides in a nearby storage space she uses as a back room. The place is peculiar: annexes of a church that were sold to an investment fund. They were going to convert it into tourist accommodation, but due to access issues the project was halted. Now, Jéssica and her mother use it as an improvised warehouse.

In Jardim do Morro, a Brazilian guy sells codfish croquettes for three euros, earning one euro per sale. The park, once known for being unsafe, has become a crowded lookout point where no bench is free at sunset. He juggles this food-selling gig with his studies in Occupational Therapy at the Polytechnic Institute of Porto. He insists his is “an honest job,” rooted in an “entrepreneurial culture.” He explains that this activity, situated in the ambiguity of informal economy, allows other migrant peers to justify minimum income and thus remain in the country.

Here, several possible explanations arise. One has to do with what we might call an ambivalent agency. Many informal workers value their autonomy—the freedom to choose their time, their space, and the manner in which they engage with tourists. They know there are limits and risks outside the legal framework, but they also recognize that formalization might require giving up precisely what makes their work valuable: its flexibility and spontaneity.

On the other hand, one cannot ignore the competitive tension with formal work. In sectors such as artisanal sales or alternative tours, informal actors compete with registered businesses. Authorities often adopt an ambiguous stance: promoting formalization but without heavy repression. It is a tacit coexistence, an unstable equilibrium that, for now, works for both sides.

In Porto, everything seems to be happening at once: tourists arriving, residents leaving, businesses emerging, others holding on. There is energy, activity, money. There is also exhaustion and resignation. The city offers itself entirely to the visitor. How much of a city remains when everything begins to be organized around those who do not stay?

And what do these people do—the ones who, from informality, provide tourist experiences? We could say they function as (and constitute) a bottom-up infrastructure. They are not tourist offices or signage, but small routines, sounds, and objects that fill the void left by those who departed. Margarida with her table; Carlos with his guitar; the croquette-seller in Jardim do Morro. They are not merely selling a product—they stage a scene that the tourist consumes. That scene is photographed, tagged, shared (and repeated). It becomes part of the landscape the city offers and that many guides and maps do not describe, yet visitors seek and remember.

They are not all the same. Some choose the street because it gives them freedom and direct contact with people; others are there because they need to supplement a pension or pay for their studies; and there are intermediate profiles combining creativity, need, and informal entrepreneurship. In this sense, we might understand informality through its degree of precariousness (do they do it out of need or choice?) and its degree of agency (can they choose their times and modes, or are they subject to pressures and risks?). This variety explains why the city tolerates ambiguous regulation. For some of those we spoke to, formalization would strip away what makes their work valuable; for others, informality is the only viable resource.

As for the role these people play in Porto’s tourism, we could highlight at least three things they do well: (1) they compose (and are) the postcard—hence a landscape/aesthetic function; (2) they create (and are) the experience—a relational function (conversations, smiles, small gestures the tourist interprets as authenticity); and (3) they sustain minimal economies (a social function), fostering income, informal networks, and forms of survival. Removing all of this would not simply mean organizing the street—it might mean transforming the very experience of Porto. Thinking this way compels us to ask not only how to regulate, but how to recognize and protect what today sustains the city so many come to visit.

International Network for Knowledge and Comparative Socioeconomic Analysis of Informality and the Policies to be Implemented for their Formalization in the European Union and Latin America

Horizon Europe Project 101182756 — INSEAI 2023 REA.A

Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions & Support to Experts A.3

MSCA Staff Exchanges